At 14 years old, a single musical experience changed my life. Like most teenagers, I was discovering the world and my passions when I first heard a piece of music so powerful that it sparked a journey I couldn’t have imagined. Listening to what I later realised was Jupiter, the majestic movement from Gustav Holst’s The Planets, changed my perspective. I didn’t know its name or composer at the time—only its grandeur. That experience planted the seed for a lifelong love of classical music.

When I told my mother, a seasoned music teacher and Royal Academy of Music alumna, about the “amazing Jupiter” I had heard, she assumed I meant Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony. For my 15th birthday, she gifted me a record of Sir Thomas Beecham conducting Mozart’s final symphony with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. As I placed the needle on the LP for the first time, the music unfolded in all its classical precision, joy, and brilliance. But something puzzled me. It didn’t have the dramatic, sweeping themes I had fallen in love with at school. I was too embarrassed to admit the mix-up to my mother, but that serendipitous mistake became the spark that ignited my fascination with Mozart.

Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony struck me with its energy, complexity, and what the French call joie de vivre. As I listened, I felt like a child—playful, profound, and seemingly effortless. With its counterpoint, the finale transported me into a world of emotional vibrancy I hadn’t yet encountered in music. What amazed me most was how Mozart, though approaching the end of his short life, composed with such exuberance and optimism. His music had a timeless quality that uplifted and deeply moved even a novice listener like me.

Years later, I still appreciate why Aaron Copland called Mozart’s compositions “spontaneity and refinement and breath-taking rightness that has never since been duplicated.”

That first Mozart record marked the beginning of a lifelong relationship with music. My journey extended into performance and understanding. At my next school, I discovered and mastered the French horn. Learning the horn was as challenging as it was rewarding, and it brought me into contact with extraordinary teachers and musicians, including Alan Civil, a renowned horn player and professor at the Royal College of Music.

Playing in amateur and semi-professional orchestras made me part of a community of people united by a shared passion for music. Performing choral masterpieces like Carmina Burana and The Messiah in partnership with choirs added a new dimension to my appreciation of orchestral music. Each piece, rehearsal, and performance enriched my connection to this art form.

As I grew older, my interest in Mozart expanded beyond his music to include the context in which he wrote. His life in the late 18th century coincided with the end of the Enlightenment, and he pushed boundaries, challenged musical conventions, and embraced new ideas of liberty and individuality. This historical backdrop deepened my respect for his achievements and made his music all the more resonant.

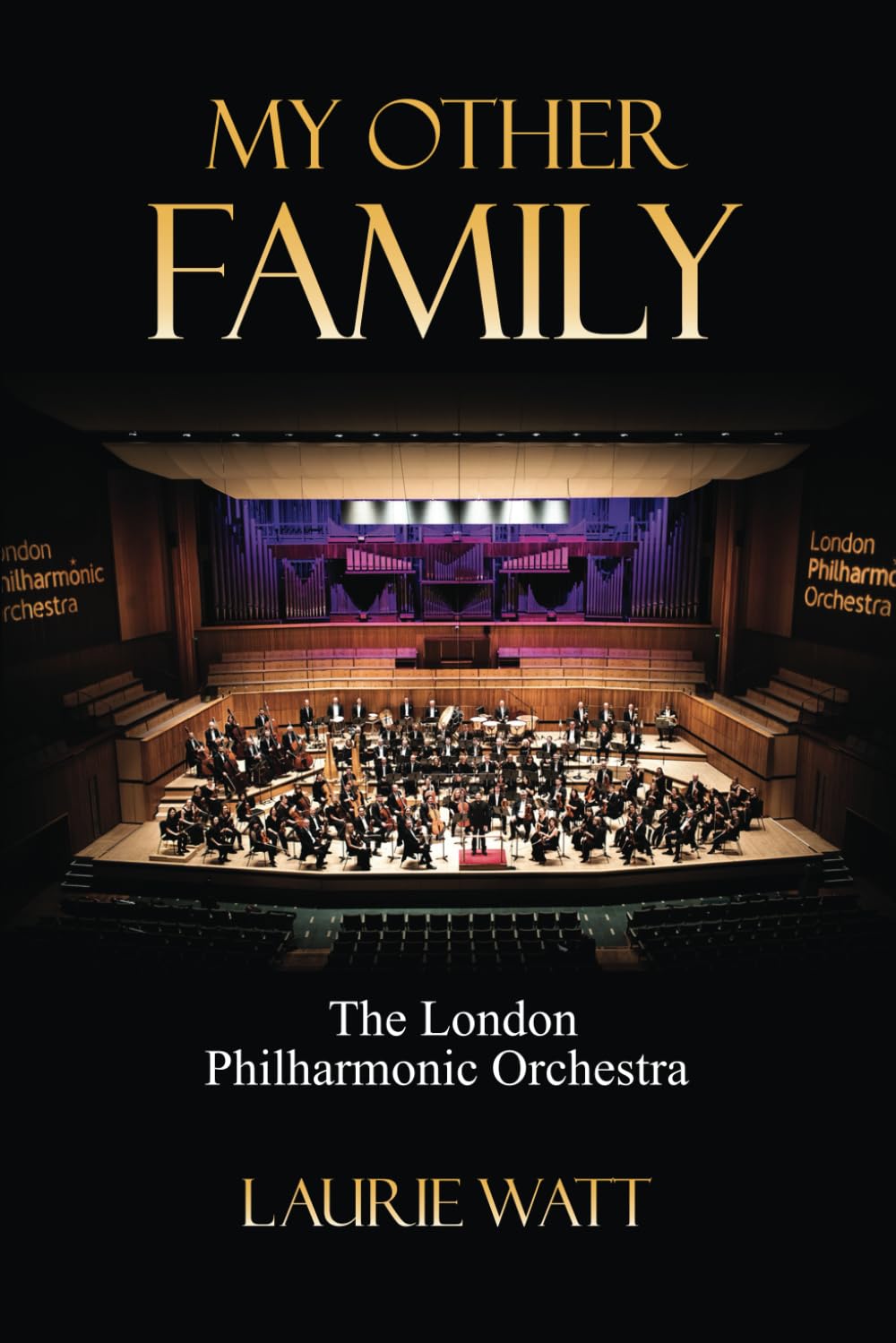

Looking back, I see my mother’s mistaken gift as a blessing that introduced me to Mozart and the boundless world of classical music. The initial misstep led me to discover Holst’s Jupiter later, completing the circle of inspiration. Today, I cherish the memory of that first LP and how it shaped my career and passion for music, which further contributed to the legacy of The London

Philharmonic Orchestra, which I (Laurie Watt) recounted in “My Other Family: The London

“My Other Family” is an autobiographical account of my life’s involvement with one of our country’s great orchestras, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, with whom I established a close relationship over nearly fifty years from the mid-1970s to the present.

Music “is a magic beyond all we do here.” For me, it has been exactly that—a source of transcendence, wonder, and meaning that continues to shape my life. For more information and insight, please visit: https://myotherfamily.co.uk/.